Cash Smith was thin on prospects and stranded inside the Astrodome when a voice wafted over the PA system, about an offer: Free seats on a flight to Denver, a place to live when you get there, help landing a job.

“You’re young, you can start over, you’ll be strong,” his grandmother prodded. Smith, then 24, boarded a plane with his two kids and other Hurricane Katrina evacuees, bound for the Rockies on a promise.

The support was real. His pregnant wife, diverted by bus to Dallas, would soon join them. A self-described "menace to society" back in New Orleans, Smith got a job at Colorado University and earned his GED. Family came, moving onto the same Denver street.

But the marriage soon frayed, he said. Relatives decamped for Texas, including his wife and kids. In Colorado, something was missing.

“They wanted that down-South atmosphere back,” said Smith, who would soon follow his family to Houston in 2010.

Smith was among the last to remain in Denver from dozens of Hurricane Katrina evacuees who had accepted the same invitation for a fresh start. All of them ultimately left, the Colorado organizers said, usually for warmer climes in Louisiana or nearby metro areas, a pattern familiar to those who have studied a diaspora that scattered some 450,000 New Orleans residents across all 50 states.

Turns out, Katrina migration was far from static or linear.

According to research released this week by Elizabeth Fussell, a Brown University professor who tracked the population shifts using closely held government data, those displaced from New Orleans kept moving around while concentrating in nearby metros, staying tethered to friends, family or other connections.

Baton Rouge and Atlanta received the largest numbers of New Orleans residents early on. But as years passed, Houston and other Texas cities began taking outsized roles in the diaspora.

Smith had been "nowhere out of Louisiana, period" before the storm, the eldest of six kids raised by a grandmother in the Iberville housing development, when he boarded the flight to Denver.

“I couldn’t adapt. The breathing. The altitude," he said. "I was not prepared for that high way of living. Then I got homesick.”

Back in Houston, he landed a job cutting grass outside George Bush Intercontinental Airport. Fifteen years later, Smith is a senior inspector for the city, with no plans to move back to his hometown.

“I’m settled here. I have a great job. I make real decent money,” said Smith, now 44. “I love New Orleans, but I didn’t have the right support to actually really enjoy New Orleans.”

The tug of home

Before Katrina and the levee failures set a population to flight, New Orleans was among the most insular cities in the U.S.

Predictably, the draw of home loomed large for the displaced. Social ties and “place attachment” were powerful engines driving Katrina migration well after the disaster, according to a report this year in Traumatology, a journal of the American Psychological Association.

“Anybody who’s lived in New Orleans gets it: That pull,” said Sofia Curdumi Pendley, a professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at New York University who led the study. “I don’t think that voice ever quieted down in people who were trying to get home.”

All told, about two-thirds of the people who were living in New Orleans before the storm were back a year later, said Fussell, who analyzed census, death and other data to track the population of those 2005 New Orleans residents over 14 years.

Many moved repeatedly. Others died. Race played a big role in where people ended up and the roads they took to get there, Fussell found.

White residents tended to return to New Orleans far earlier than Black residents, a fact that studies have linked to more severe housing damage at lower elevations for Blacks, and a slow and biased Road Home recovery program, among other factors.

Black residents also tended to be "much more likely to be mobile and go in and out" of the New Orleans area afterward, Fussell said.

The gap eventually narrowed, with more than 80% of Black New Orleanians returning to live in the metro area at some point by 2019, according to the research.

But Fussell also found big differences in what happened then. Displaced Black residents were more likely to be mobile, more often toggling between New Orleans and other locales.

“One of the big lessons from Hurricane Katrina is that a disaster that destroys housing and displaces people like this creates more mobility over a lifetime,” she said. “People move, not only because of the hurricane, but perhaps because the place they ended up wasn’t the place they want to be.”

Four Southern cities vied as top destinations: Baton Rouge, Atlanta, Houston and Dallas. But their ranks changed over time, Fussell found. Houston and Dallas have added more Katrina migrants since 2005, while Baton Rouge and Atlanta have shed them.

Fussell, a professor at Tulane University when Katrina struck, said a “friends and family effect” guided migration on tracks laid before 2005, when departing Louisianans followed a robust Texas job market.

"The connections that were already there were helping to bring even more people to those places,” she said.

The research also showed that Atlanta, Houston and Dallas were more attractive to Black New Orleanians who were displaced by Katrina than for non-Black residents, by a margin of more than two to one.

Leaning on connections

Beatrice Soublet, 81, at her home in East Point, GA, on August 11, 2025, where she now lives after leaving New Orleans because of Hurricane Katrina.

To Beatrice Soublet, staying in Atlanta only made sense.

She'd just retired as principal of a 9th Ward grade school when Katrina threatened. Her then-fiance, Lawrence Soublet, was retired from the New Orleans Sewerage & Water Board and “knew what would happen if things went the wrong way,” she said.

They left in two cars for Dallas, staying a few days.

“I woke up one morning: ‘Why am I paying money for a hotel here when I have a daughter in Atlanta?’” Soublet said.

The family connection steered them east. The couple soon found a church in Atlanta with suitable music, and a school, Hope Hill, where they could volunteer.

Now 81, Soublet still keeps around the 2003 Corolla that she wheeled out of the city with an aunt and her black cat, Madagascar. Trips to New Orleans are shorter now, to see her childhood friend Yvonne and seek out gumbo and oysters at Dookie Chase's.

She choked up recently as she counted her Katrina losses: longtime friends, church at St. Peter Claver, her “sweet little house on North Roman,” breakfast on Bayou St. John.

Soublet stayed in Atlanta because Lawrence had received a kidney transplant and worried about health care in New Orleans. He passed in 2021.

“He didn’t want to dodge a bullet," she said. "I stayed here because Larry stayed, and then we got married, and this was our life. You make yourself at home because home is up inside of you, you know?”

Georgia on their minds

Normicka Forest, wearing a t-shirt she designed, at her home in Atlanta, GA, on August 11, 2025, where she now lives after leaving New Orleans because of Hurricane Katrina.

For most, the reasons for staying away from New Orleans were complex and varied: home, jobs, education and health factored in. Children were least likely to return in the early years.

“A lot of people were much better off somewhere else, and good for them. It was awful,” said Tulane demographer Mark VanLandingham. “(The storm) provided an opportunity for people to see what else might be out there.”

For Normicka Forest, an Atlanta suburb was an immediate safehaven.

But a visit home just weeks after the storm sealed her decision to stay in Georgia. Forest found her apartment in the B.W. Cooper housing development caked in mold. The new paint job, the Spiderman-themed bedroom, the aquarium bathroom with fish. All of it wrecked.

"It was rough. The waterline. I didn’t want to believe it,” she said. “There wasn’t a bone in my body yesterday, now, tomorrow, that said I was moving back home.”

As Katrina approached Forest planned to stay in town -- ''You know the saying whenever there’s a storm: the bricks aren’t going anywhere" -- but instead joined a family caravan crawling east. At a crammed hotel outside Atlanta, she got word of public housing 70 miles northwest.

“I went to the receptionist at the hotel and said, print me out a map to Rome, Georgia,” she said. “I stayed in Rome for six years.”

Forest enrolled at Georgia Highlands College and began enlisting friends to join her, forming a small New Orleans outpost.

“I really recruited a lot of people... It was a nice chunk of people. There were some Katrina evacuees, all from the same community I was from,” she said.

Some moved home. Forest moved to Atlanta for a job with the state juvenile justice agency, where she works as a budget analyst.

She's proud of the moves she’s made in Georgia, while still efforting to keep New Orleans close. She recently launched a business, Nola's Peach Kreations, aiming to market products on the side.

“It’s like a spin on the New Orleans I came from," she said. "And where I ended up.”

Feels like home

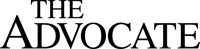

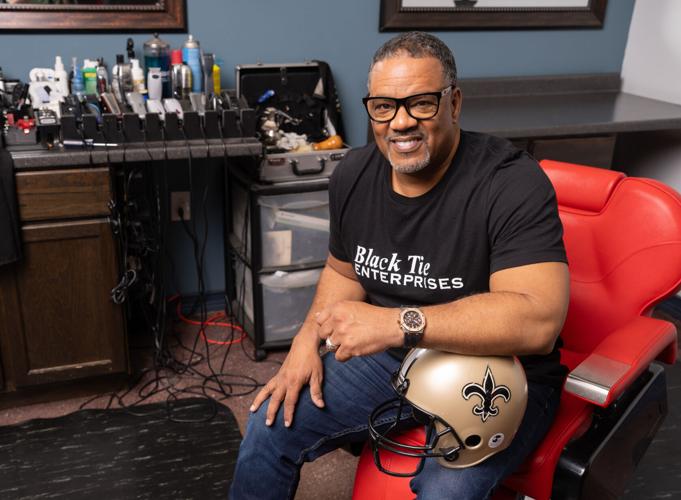

Mark Fortier, with his daughter Micah Fortier, 19 at his barbershop, Black Tie Barbershop, in Buford,GA, near where they now live after leaving New Orleans because of Hurricane Katrina. Mark's wife Arnell was pregnant with MIcah when the left New Orleans and she was born shortly after they arrived in Atlanta. August 11, 2025. Photo by Michael A. Schwarz.

A hundred miles east of Rome, Mark Fortier has tried to keep a New Orleans beat going in Buford, a city of 17,000 that just opened a $62 million high school football complex.

“To want something different and to actually attain it, a lot of times you have to remove yourself from certain situations,” said Fortier, 60, a barber and DJ from the 7th Ward.

He'd packed up a pregnant wife, a set of hair clippers, his Akita, MawMaw, and enough clothes for a few days, thinking of a short stay away.

“They were trying to take us up (Highway) 59. I said, ‘Ima take this right turn,’” said Fortier, who had lived for a stint in Atlanta. “We literally drove the shoulder of the freeway from Mississippi to Georgia."

Fortier said he left behind a “checkered” criminal past in New Orleans, then bounced between barber chairs from Buford to Atlanta before opening his own shop.

For a while, he helped set up shows through a group called New Orleans Connection, and popular tailgates near the Georgia Dome for Saints-Falcons games.

"I created an environment of New Orleans culture to feel like home, not being at home," Fortier said, though there’s less of that activity now.

“Some people moved back to New Orleans. The crowd that was attending those parties 20 years ago, now they had kids also, and they had lives,” he said. “Everything runs its course.”

In Georgia, Fortier said he's cut hair for star ballplayers and appeared on Real Housewives of Atlanta. His daughter Micah, a Katrina baby born in early 2006, is now a sophomore at Kennesaw State.

"If you ask her where she's from, she says New Orleans," said Fortier, who chuckled at the sentiment. "My whole not being in New Orleans is because of her. You have to embrace that change. And you have to want a little bit better.”