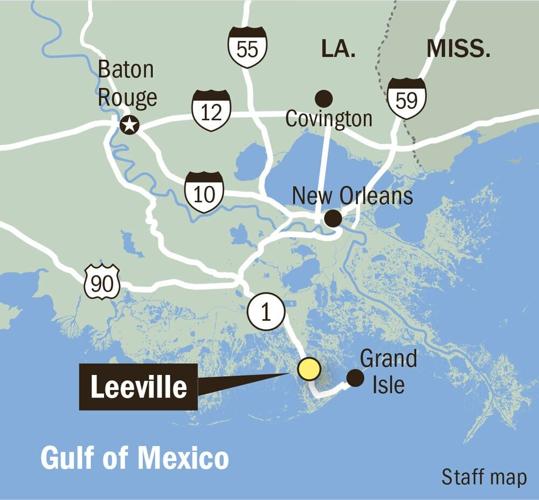

As Phyllis Melancon drives down La. 1 toward the Gulf of Mexico, her husband Timmy points to where lost landmarks used to be: a bait shop, a chapel, their family home.

For the couple in their late 60s, married when they were 14 and 15, each site evokes stories of family members and old friends in the town of Leeville, which has lost nearly all its land and people over recent decades.

“Since the last storm, there’s no more gas stations, no more restaurants,” Phyllis Melancon said of 2021’s Hurricane Ida.

“It’s just a road,” Timmy Melancon said. “That’s it.”

Leeville is at the forefront of Louisiana’s coastal land loss crisis, which has robbed the state of land the size of Delaware over the last century — among the highest rates in the world. In 2021, Ida destroyed what was left of the small fishing village. Today, around three people live in Leeville.

Wind and water damage caused by the path of Hurricane Ida Tuesday August 31, 2021, in Leeville, La.

The problem has long been a priority for the state, and now the NFL is lending a hand ahead of next weekend’s Super Bowl. On Monday, a group of special operations veterans left the bustling pre-Super Bowl streets of New Orleans for the quieter landscape of Leeville, where water laps against the highway.

After the two-hour drive down La. 1, ex-Navy Seals, restaurant workers, Chalmette High School students and other volunteers installed an oyster reef and planted marsh grasses as part of an initiative involving the nonprofit Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana, or CRCL, government agencies, global corporations and the NFL’s sustainability program. The effort will extend beyond Monday, as CRCL is trying to secure funding for a larger reef.

Taking a break from reef building, the more than 150 volunteers ate fresh oysters from only a few miles away.

The first part of the project began in December, when dozens of volunteers gathered to divide 59 tons of oyster shells from restaurants into mesh bags — the smaller units that compose the reef.

"I'm kind of speechless," Megan Champagne, the coastal zone management administrator for Lafourche Parish, said. "We've never had such a big agency collaboration."

Emma Willis, a senior at Chalmette High in her school's environment club, said the project brought to her attention that people are trying to address the coastal crisis in Louisiana. Before, she only knew that the land was disappearing.

The new "living shoreline” will not bring back Leeville. No one is under any illusions about that.

Mel Sumer, Native Plant Program Serve Louisiana Coordinator, catches a plug of spartina grass at the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana and ‘NFL Green’ oyster shell installation in Leeville.

But the faded community near Grand Isle is still a popular fishing spot, and its remaining land helps provide protection for locations farther inland. The reef will assist on both of those matters.

"We get the ability to do a living shoreline project and also bring awareness to the nation of everything that we do," Glenn Ledet, executive director of the state's Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, said.

Besides protecting the shoreline, it will invigorate the aquatic ecosystem around the Theogene B. Melancon boat launch, named for the first person to open a boat launch in the town, his great-grandson Tee Tim Melancon said. Alongside the veterans and coastal organizations, some of the families who hailed from — and then ultimately fled — the small Cajun town also observed the reef installation, evoking complicated emotions.

“Every storm since we were born, we went through them all,” Phyllis Melancon said ahead of the event. “And then this last one, Ida, was the worst out of the 67 years that I’m alive. She was the worst that you could have, because the others we cleaned, painted and repaired with little. This one, there was nothing left to repair. There was nothing to come back to.”

Ida washed away the home they had lived in for decades, elevated above the bait shop that Phyllis ran. Timmy Melancon said the same happened to his grandfather’s house of 100 years and his uncle’s house of nearly 80 years.

“And we didn’t cry,” Timmy Melancon said. “Not once, nothing. We just went on with our lives. We were raised like that.”

They had endured so much already, Phyllis Melancon explained. When Katrina hit Leeville in 2005, the house she grew up in with her parents and seven siblings was severely damaged.

“And then Rita (a few weeks later) ... and it washed away," she said.

After each storm, the couple, who did not have insurance, would clean up and start again.

‘Your livelihood erodes away’

The onslaught of storms led to the dwindling population of Leeville, which sits beyond the levee system eight miles from the Gulf. But Leeville itself is disappearing, too. Land that once held citrus groves and cotton fields is not much more than a narrow street.

Workers and volunteers form a line to build a reef with oyster shells near the Theogene B. Melancon boat launch in Leeville. During phase one of the reef building, 59 tons of oyster shells from restaurants were used to begin the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana and ‘NFL Green’ oyster shell installation.

Parts of Leeville have dropped around four feet since 1900, said Windell Curole, who led the South Lafourche Levee District for four decades. Golden Meadow, where the Melancons relocated, is not much different. Curole said a 1982 study found the highway in Golden Meadow 1.3 feet above sea level. Now, the same spot is 0.3 feet above sea level.

Curole lives north of Golden Meadow in Cut Off, but he has strong Leeville ties — his great-great grandfather, Pierre Lee, gave the town its name. Over the last 100 years, Leeville has lost around 90% of its land, Mike Biros, CRCL's restoration programs director, estimated.

Wendell Curole at the Leeville Cemetery off of La. 1. Concrete was poured to try and save the cemetery but high tides and storms frequently cover the area.

Land sinking, called subsidence, is driving the disappearance. The levees constraining the Mississippi River protect communities from flooding but deprive the delta of sediment to rebuild land and sustain itself. Subsidence is the biggest factor in the region’s land loss, Biros and Curole stressed, but there are others too.

Global sea level rise, faster in the warm Gulf waters, heightens the problem and is projected to worsen. Saltwater encroaching from the Gulf destroys the delicate wetland ecosystem, and canals dug for oil and gas exploration accelerate saltwater intrusion, Biros noted.

“Naturally, your income, your livelihood erodes away,” Tee Tim Melancon said. “You can’t live off the land if the land’s not there.”

A safe haven

The pattern of rebuilding and relocating has been passed down through the generations. The town was founded by survivors of the 1893 Cheniere Caminada hurricane, which destroyed the small fishing community of Cheniere Caminada and killed around 2,000 people.

For the founders, Leeville was a safe haven, Bren Hasse, the director of the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program, explained.

Leeville as seen on April 18, 2021.

“It was higher ground, it had lots of wetlands around it for buffer,” said Haase, the former head of the state’s coastal protection agency.

Located between some of the most abundant estuaries in the world, Leeville boasted lifelong fishers and shrimpers, like the Melancons. A few decades later, it became the oil capital of Lafourche after a big find in the 1930s.

Timmy Melancon described an ecosystem where the two industries — oil and fishing — complemented each other, if not environmentally than communally and economically.

“Every gas station had a little deli and breakfast in the morning because everyone needed to pass through Leeville on the way to work,” he said.

The Leeville Cemetery off of La. 1 on the west side of Bayou Lafourche.

Leeville is one of the last stops on the way to Port Fourchon, which accounts for around 15% of the country’s oil supply and helped provide the local fishing industry with reliable business. In 1999, Mike Tidwell, a travel writer with The Washington Post, hitchhiked aboard fishing boats in the area, chronicling how land loss endangered coastal communities for a popular book, "Bayou Farewell.”

Back then, Tidwell said, Leeville was a functional community. There was Griffin’s cafe, Phyllis Melancon’s bait shop and a cadre of working shrimpers and crabbers. Lots of land had already been lost — the town looked nothing like the childhood homes of the elder Melancons — but “there was some bustle there,” he said.

The Leeville population is a bit under dispute. Curole said that a couple hundred Cheniere Caminda survivors likely settled in the town. Phyllis Melancon said that at one point, a population sign in the town said 3,600, but Tim Melancon said there was no way it was that high. Curole recalled the population being around 60 in the mid-20th century.

The town’s relatively small population was boosted by the steady stream of industry workers, fishers and camp owners passing through.

“I miss meeting people that would come to the shop,” Phyllis Melancon said. “Near the water, having our shop, that’s what I miss — the people.”

In 2011, the elevated expressway from Leeville to Port Fourchon opened, and it will eventually extend to Golden Meadow. This means that people driving to the Port and Grand Isle can bypass the near-empty town.

“It’s a working coast, and we have retreated from that but continue to work there, so we have to travel further,” Curole said. “But it was also part of our culture being right there near the resource, and that made us a little bit different in that you could be dirt poor but then you eat freaking well.”

‘It’s almost who I am’

Fourth generation born and raised in Leeville, Tee Tim Melancon and Jerry Martin left their hometown for better opportunities. In their 40s and 50s, respectively, they both work at Edison Chouest Offshore in Galliano, around 20 miles from where they grew up.

For Melancon, he didn’t see opportunities for himself if he stayed and followed his parents’ path.

“You looked at your parents, they were barely paying the bills, there was nothing new for you if you stayed,” he said. “It’s a culture you’re losing as well. It’s a way of living. It’s almost who I am.”

Jerry Martin’s mom and stepfather are two of the approximately three people still living in Leeville. And their presence in the desolate town upsets him.

“They don’t leave for storms. They stay there and they weather it,” he said. "It makes me kind of nuts. Like, what are you guys doing? You can’t win this fight.”